‘Stalin’s Master Class’ of cultural oppression at Odyssey Theatre

- Anita W. Harris

- Apr 30, 2024

- 3 min read

Though billed as a comedy, the Odyssey Theatre’s “Stalin’s Master Class” by David Pownall is more like a lively character portrait of Joseph Stalin, the dictatorial Soviet premier from 1924 to his death in 1953.

Directed by Ron Sossi at a steady pace of tension, the play focuses on a single night during a 1948 music conference when Stalin and his culture minister hold two composers practically hostage at the Kremlin in getting them to bend their art toward government interests.

With such fascism potentially on our own horizons come November — women’s freedom of choice already increasingly circumscribed, leading to more women and babies dying in restrictive states — it’s perhaps timely to experience a dictator’s mercurial bullying on stage for a taste of what might come.

Composers Sergei Prokofiev (Jan Munroe) — whose works include the “Romeo and Juliet” ballet — and Dmitri Shostakovich (Randy Lowell), whose moody compositions express the oppressiveness of his times, are invited to the Kremlin to meet with culture minister Andrei Zhdanov (John Kayton) and Stalin (Ilia Volok) during one evening of the Soviet conference of musicians.

Though this meeting was imagined by Pownall for his 1983 play, in real life both composers were among six censored by the Communist Party during the conference, their “formalist” music denounced as too desolate and divorced from the people compared to more populist pre-Revolution music.

Seated stiffly on an ornate couch in the Kremlin office of Zhdanov donned in military khaki, the more seasoned Prokofiev in a dapper suit and younger Shostakovich in a red sweater and jacket (costumes by Mylette Nora) are visibly nervous — the former throwing up from anxiety in the bathroom while the latter slams back the vodka shots Stalin offers.

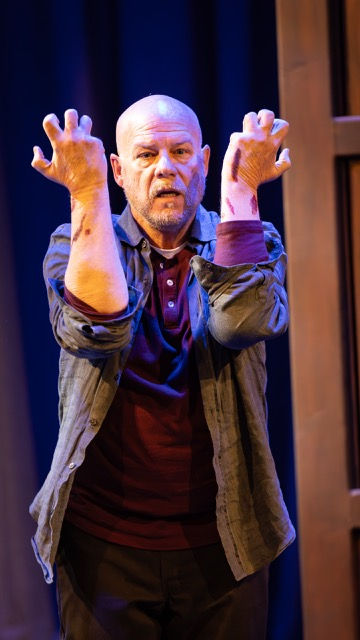

Simply dressed in black pants, boots and untucked white shirt, the mustachioed Stalin (looking a bit like actor Pedro Pascal) proceeds to play cat-and-mouse with the composers, similarly to the couple toying with unsuspecting guests in Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” — a 1962 play to which Pownall’s has been compared.

Alternately cordial and bullying toward the musicians while becoming increasingly drunk, Stalin reveals himself during the course of the play to be a figure more complex than “tyrant” might suggest.

He knows something of music and attended a seminary in his native Georgia — an idyllic, pastoral state he nostalgically reveres — wanting to become a priest until he was expelled, just as he was later exiled to Siberia for protesting the Czarist regime, where he revels in the primal behavior of wolves.

A wooden triptych icon features prominently in the play to which Stalin offers vodka, pouring it over the figure of Jesus. He pushes the cane-dependent Prokofiev to the floor in asking him to choose his favorite recording before he and Zhdanov smash all the records in a fit.

In perhaps the most darkly comic scene of the play, all four men compose a song on the piano trying to capture the idealism of both Georgia and the Revolution — only for Stalin to be devastatingly disappointed when it’s played back by the secret Kremlin recorders. We see him curl up on the couch crying, demanding the others avert their eyes.

While not a likeable person, and menacing in his unpredictable moods, Stalin here is not unsympathetic because we see his personal side, learning of the extremes he endured and passion for his ideals.

Ultimately, though, Stalin says he was responsible for the deaths of 20 million Russians in World War II. And he always seems a breath away from killing the two intimidated composers locked in the room — Prokofiev frail and frightened, Shostakovich emotionally tearful.

The play thus offers a compelling master class in Stalin himself, whom Volok embodies intensely and believably throughout. Music certainly figures as well, aided by pianist Nisha Sue Arunasalam offstage. And dialogue on whether music can be shaped by artists or only serve the public interest is intriguing — and scary to consider with our own artistic and other freedoms on the line.

“Stalin’s Master Class” continues at the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble, 2055 S. Sepulveda Blvd.,

Los Angeles, through May 26, with performances Wednesday, May 15, at 8:00 p.m., Fridays at 8:00 p.m., Saturdays at 8:00 p.m. and Sundays at 2:00 p.m. Tickets are $35 or pay-what-you-can on Fridays. For tickets and information, call the box office (310) 477-2055 or visit OdysseyTheatre.com. Run time is 2 hours and 10 minutes, including intermission.

"20 million people" refers to the number of Russians who died during World War II.